About Echinacea

Purple coneflower (Echinacea angustifolia) and other Echinacea species have been the most widely utilized and important medicinal plants used by Indigenous people of the Great Plains. The plant is still being harvested and used traditionally today in many tribal communities. Lewis and Clark learned about it during their expedition and in 1805 and shipped the roots and seeds back to President Jefferson as one of their more important finds.

Echinacea pallida, with longer petals, and Echinacea angustifolia, with short petals are the two species that have been harvested significantly from wild populations.

Euro-American medical botanists recognized Echinacea in publications as early as 1830. Echinacea angustifolia was introduced to medical use in “Meyer’s Blood Purifier” in 1885 by the folk doctor H. C. F. Meyer of Pawnee City, Nebraska. By the turn of the century, the plant was well established among the Eclectics, a group of physicians who emphasized the use of medicinal plants in their practice, and widely used by “regular” doctors. Echinacea angustifolia was the most-prescribed medicine made from an American plant through the 1920s, declining only upon the introduction of sulfa drugs and antibiotics.

Echinacea angustifolia, native to the tall- and midgrass prairies of North America, has been commercially harvested for its medicinal properties for more than 120 years. Though all Echinacea have some medicinal qualities, the roots, leaves, and flowering tops of three of the nine Echinacea species are important in the modern herbal medicine market: E. purpurea, E. pallida, and E. angustifolia.

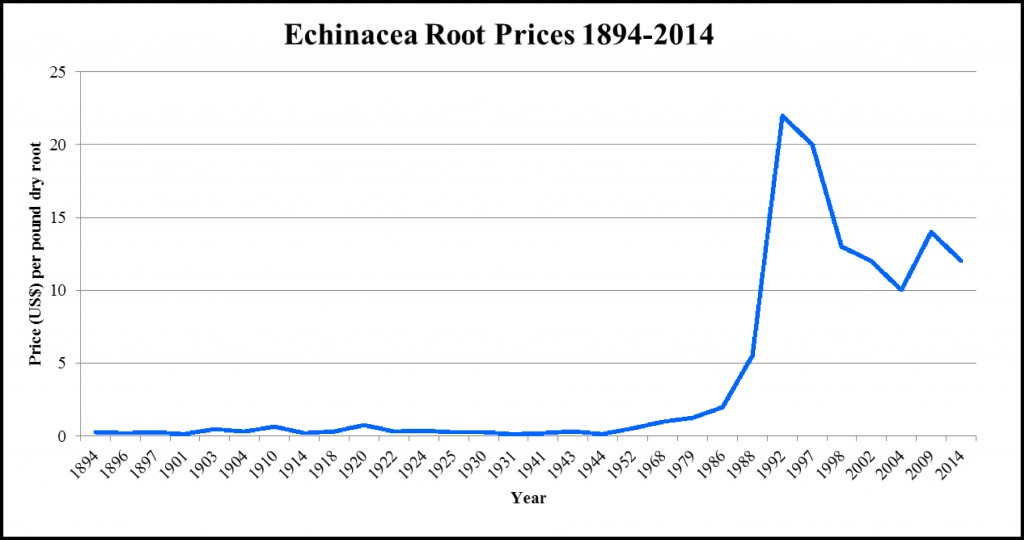

Prices paid to diggers of wild harvested Echinacea angustifolia root in the Smoky Hill region of Kansas during the last 120 years.

Echinacea extracts, tinctures, and capsules have become popular as immune stimulants with consumers in North America and Europe. There has been considerable debate over the identity of the specific constituents which are responsible for the biological activities of Echinacea species. The list of chemical constituents reported from Echinacea is long and includes alkamides, caffeic acid derivatives, glycoproteins, and polysaccharides, which are likely responsible for its immunostimulatory properties. Clinical trials show positive benefits in its use as a treatment for upper respiratory tract infections, including the flu. Unfortunately, few clinical studies to establish accurate and effective dosing of Echinacea have been conducted. In addition to its extensive history of safe use among North American indigenous groups, clinical research has shown that Echinacea is one of the safest herbal products on the market, with only a very slight risk of allergic reaction or adverse interactions with some medications.

Overharvest of at-risk wild populations of Echinacea, particularly of rare species, can become a sustainability concern in some areas, especially when the market price is high and other local economic opportunities are few. Public lands, such as state parks and U.S. Forest Service lands can quickly become prime targets for unlicensed poachers looking to capitalize on a peak market price. Consumers often prefer wild-collected products over farmed medicinal plants, driving the value and demand for wild Echinacea up. Overgrazing by cattle and broadcast spraying of broadleaf herbicide on rangeland also threaten Echinacea populations. Loss of habitat as land is converted to agricultural crops or developed for housing, commercial, and industrial use poses a far greater risk to the sustainability of all Echinacea species populations than overharvest.

Because most Echinacea is harvested for the root, plants will either die or be greatly stunted from the harvesting process. The largest plants with the most flower stalks also have the largest roots, making them the preferred target for harvesters. Unfortunately, these large plants are also the best seed producers, so the loss of these mature plants also represents a great loss of seed potential for repopulation in harvest areas. Informal observations by harvesters and researchers suggested that a significant proportion of harvested plants, even if the root is dug quite deep, will resprout from remaining root fragments.

Resprouted Echinacea angustifolia root from the Smoky Hills in north-central Kansas, showing larger, original root on right, and then the joint in the middle with the immediately smaller root to the left attached the leaves, that is from where the resprout started growing again, from where it was previously harvested, approximately three years before in this case.

In 2003 we began a study on rangeland populations of Echinacea angustifolia in Kansas and Montana, harvesting mature plants to a typical harvesting depth of approximately 6-8 inches. We returned to the same harvest sites one and two years later to survey which dug plants had resprouted. Some of the plants dug up during our initial harvest in 2003 showed obvious evidence of being a resprouted plant already from a previous commercial harvests. After two years, in 2005 we redug all of the resprouted plants from our research area, digging deep enough to extract the root below our previous harvest depth, revealing the larger remnant root below our severance point and the slender resprouted root.

In cooperation with the United Plant Savers, a non-profit organization dedicated to the conservation of medicinal plants, we have determined that the risk for overharvesting of Echinacea angustifolia ranks only as moderate at this time, though ongoing evaluation should continue as market demand fluctuates and habitat loss increases. The characteristics of high seed production and approximately 50% resprouting of harvested plants means that it is possible for populations to persist despite periodic commercial harvesting.

For more information on this work, see: http://nativeplants.ku.edu/research/at-risk-plants